Finding a Balance Under Pressure

The pressures and stresses of undertaking a PGR project can make it harder to achieve a work life balance. However, it is important to still try and there are many different ways to approach doing so [1]. Maintaining a work life balance will be better for both your wellbeing and your work. To achieve a healthy work/study/life balance, there may be a few ‘trade-offs’, but that is OK [1].

There are a number of strategies that students can find helpful.

- Purposely managing your time, prioritising tasks, responsibilities and different roles to ensure that you have a good balance.

- Creating and protecting personal time. This can help to maintain mental and physical health and has been shown to help manage stress.

- Seeking out support from the university, friends and family [1]

The pressures that PGR students experience may come internally or externally.

Internal pressure can arise from pushing yourself too hard, having unrealistic or overdemanding expectations of yourself and worrying that you will not meet the expectations of others. These feelings may be linked to imposter syndrome.

Clance (1978) coined the phenomenon imposter syndrome and found many successful individuals ascribe their success to external factors. Imposter syndrome fosters feelings of being a fraud and unworthy of promotions or rewards. The feeling of success and feeling capable of doing well are inhibited, even if they have external praise. Individual’s experiencing imposter syndrome may place enormous pressure on themselves and display high levels of perfectionism and workaholic behaviours [2].

Imposter syndrome has been found among many students doing a PhD and different emotional and intellectual challenges that PGR students face, can result in feelings of intellectual inferiority [3].

Several studies have found that it is important for researchers’ development to have positive emotions and feelings about themselves as researchers [4]. Kiley (2009) suggests that this development of emotions and feelings is a process of learning to be a researcher. This can include understanding of specific research concepts, such as framework, theory or data analysis. Imposter syndrome can affect a PGR student’s wellbeing if this feeling continues [5].

External pressure may come from the people around you or the circumstances in which you find yourself – an approaching deadline, a meeting that you need to feel prepared for or financial difficulties.

Unfortunately having too much increased pressure can be counterproductive and when the pressure exceeds a comfortable point, our performance begins to decrease and suffer [6]. Not only does our performance suffer but our mental health can also decrease, and we may become stressed, anxious and unhappy. Furthermore, this could lead to burnout, which is a chronic response to emotional and interpersonal stress within a job. It is caused by excessive and prolonged stress, and produces emotional, physical and mental exhaustion. Burnout may occur when there is a constant demand, and you feel overwhelmed and emotionally drained [7].

However, if the pressure is internal or external, there are strategies to help to thrive under pressure.

Thriving Under Pressure

- Coping with pressure and improving your wellbeing can be supported by eating healthy, regular exercise, and getting enough sleep. We go further into these in “Physical Wellbeing and Academic Performance“.

- Develop an internal locus of control. Although we cannot control every aspect of our lives, the way we think about ourselves and our lives has major consequences for our wellbeing. Internal locus of control is the belief that you are in control of your destiny or own fate. This feeling of control has been shown to be good for you mentally and physically. For example, A study by Sinha, Bhattacharya and Sharma (2019) [8] found that workers with a strong internal locus of control had higher job satisfaction and lower job-related stress. Luckily there a number of options to help increase your internal locus of control:

- Pay attention to areas of your life where you do have control – often we can be carried along by automatic behaviours, habits or the assumptions of others. Stopping to identify if you have more control over a particular circumstance, can help you realise that you have more power than you first assumed. This in turn can help strengthen your internal locus of control.

- Pay attention to the choices you have. It may feel like you don’t, but you usually do have a choice of some sort. The choices available may not be your first choice (you may not even feel they are good choices), but there are usually still different options open to you. Exercising choice can help you feel more in control of a problem – even if this doesn’t make it good.

- Write down all of the different options you may have. Think about what you can control and change.

- Think about what is best for you and the best course of action for you.

- Practise letting go of what you can’t control. Deliberately deciding to let go of something is often the greatest exercise of control and is very different from feeling that something is being taken from you.

- Pay attention to areas of your life where you do have control – often we can be carried along by automatic behaviours, habits or the assumptions of others. Stopping to identify if you have more control over a particular circumstance, can help you realise that you have more power than you first assumed. This in turn can help strengthen your internal locus of control.

- Work on being as organised as you can. Use structure, routine and planning to help you – trying to make the day work without a plan or routine, increases the number of decisions you have to make and exacerbates feeling out of control.

- Using a positive mindset to motivate yourself (See “Maintaining Motivation“)

- Never be afraid to ask for help. (See “Finding Out What Support is Available“)

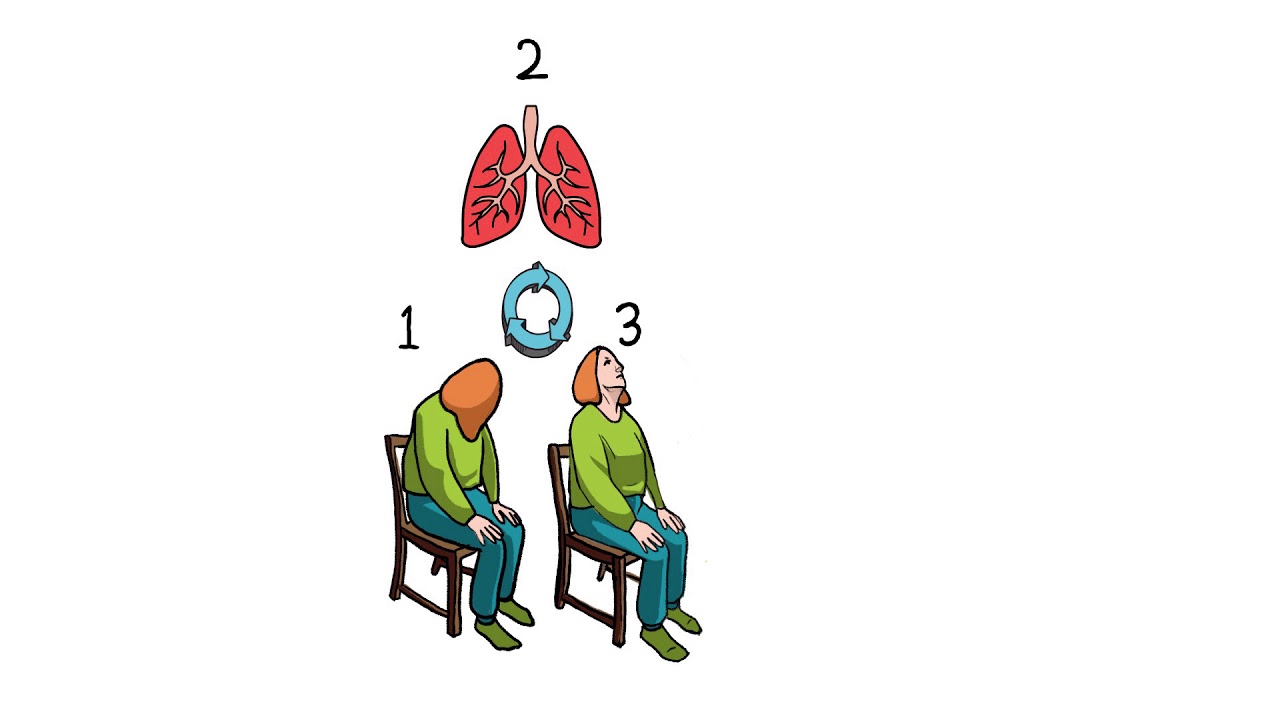

- Take a mini-break

- Visualise yourself as already having achieved and successfully working past the pressure that you are under. The ‘Best possible self’ exercise [9] has been found to a successful tool for increasing wellbeing. It involves imagining yourself in the future, and everything has turn out the way you would like it to. Imagine that you have fulfilled all your life’s dreams and developed to the best possible potential. This could be in the area of personal, relationships and/or professional aspects of your life. Then thinking about this life – write down your manageable goals, skills and desires. Spend 20 minutes doing this to really allow the benefit of the exercise to sink in [10].